- Diaspora

- No Comment

Caught Between Two Cultures: Diasporans face mental-health struggles in trying to adapt

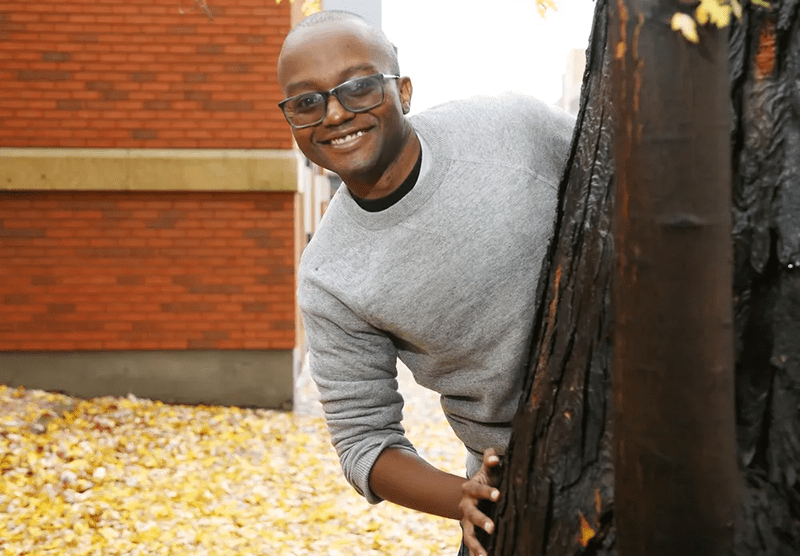

CANADA: CJ Ndiweni wants people to feel comfortable mentioning mental health and immigration in the same breath.

The 30-year-old moved to Sudbury earlier this year with his mother and sister after coming to Canada as a refugee in 2008. And although he has been a Canadian citizen since 2014, he says he feels caught between two cultures and often struggles with a poor sense of belonging. Ndiweni wanted to share his story in hope that it will spark dialogue on an issue not often discussed, especially among newcomers.

“Canadian society has a way to remind you that you don’t fit in, in subtle ways,” he said.

Ndiweni said that while it’s difficult to watch and read the news about the country’s affordable housing and homelessness crisis, it’s unfair to blame immigrants for the dilemma.

Behind the headlines, Ndiweni sees the pain — and trauma — that many new immigrants are experience after fleeing a war-torn country or leaving home. This trauma, he says, will be buried for the time being as newcomers focus on basic survival needs like shelter and food.

“But it will keep building up until the day it explodes,” he said.

Ndiweni’s immigration story starts earlier than his arrival in Canada, however, as his family left Zimbabwe for the southern U.S. when his father secured a student visa to study at a university in Texas. Sadly, his father passed away and the family lost their status. They faced deportation and after several attempts to remain in the U.S., his mother decided to pack up the car and take the family to Canada. They were successful in entering the country as refugees and eventually settled in Kitchener, Ont.

Ndiweni said he’s always felt the pressure as an immigrant child to fit in and as a male in his culture, didn’t feel comfortable sharing his feeling.

“For the African diaspora, there is a struggle to hold onto our culture but to adapt,” said Ndiweni.

Struggling to fit in

After high school, Ndiweni went on to work in numerous jobs, from manual labour to the non-profit sector. But he struggled with fitting in and became depressed, ultimately leading him down the road of a 10-year battle with addiction.

“I’ve been two years sober and it was through reaching out for help and the support of people close to me that I was able to start rebuilding my life again,” he said.

Living in Northern Ontario is a “breath of fresh air” and he is considering pursuing a university degree in psychology.

Karen Hourtovenko is a psychotherapist based in Sudbury. She doesn’t treat or know Ndiweni but sees clients who live with various forms of mental illness, including those that have experienced trauma. She says isolation is the key factor that leads to mental distress.

“When people leave a country to another, when it is by choice, because they are coming for a job opportunity and they are being transferred and supported that way, then those people are already connected to a community,” she explained. “But there are many other people that come because they are fleeing.”

She said most people are leaving trauma when they flee a country and claim refugee status.

“People who have mental distress and have trauma, their mind constantly plays over and over and over the trauma, which then creates more emotional distress even though they are not in it.”

Hourtovenko said they walk around in fear because they don’t know who to trust or whether they are safe. If they are unable to find housing, pay for food or find employment, that compounds their fear and could lead to more isolation, she said.

Emotional distress

“When people leave a country to another, when it is by choice, because they are coming for a job opportunity and they are being transferred and supported that way, then those people are already connected to a community,” she explained. “But there are many other people that come because they are fleeing.”

She said most people are leaving trauma when they flee a country and claim refugee status.

“People who have mental distress and have trauma, their mind constantly plays over and over and over the trauma, which then creates more emotional distress even though they are not in it.”

Hourtovenko said they walk around in fear because they don’t know who to trust or whether they are safe. If they are unable to find housing, pay for food or find employment, that compounds their fear and could lead to more isolation, she said.

Many cultures see mental illness as a weakness, she said, and there is far more stigma for a man to be mentally ill than a woman.

“If you come from a culture where how you show up in the community is important, then you become the black sheep of the family,” she said. “So why would anyone say they have a problem? But we see this in all cultures because it is a stigma. But if we saw this as mental injury and we look at it as an injury from trauma, then people would be more comfortable and say they need help.”

Hourtovenko said everyone shares a responsibility in ensuring newcomers don’t feel isolated.

“Churches do a great job in bringing people in for that welcoming,” she said. “There are community events that are often free … If we are welcoming people into our community, then we as community members owe it to these people to help them feel welcome. We all have a role to play.”

Every human life has value, she said, and we must realize that each newcomer has the capacity to contribute to our community in a meaningful way. Often counselling and therapy are necessary, but never underestimate the power of fostering a sense of community and connection, said Hourtovenko.