- Opinion

- No Comment

Zim Researcher: UK creates ‘hostile environment’ for African sexual and gender diverse asylum claimants

By news.uct.ac.za

Increasingly people are fleeing their countries of birth to seek refuge elsewhere in the world. And the reasons are plentiful – civil war, political instability, poverty due to high levels of unemployment, and serious and violent crime. But gender-diverse people flee their counties of origin too because of sexual and gender discrimination, and are seldom embraced upon arrival in their new, would-be homes.

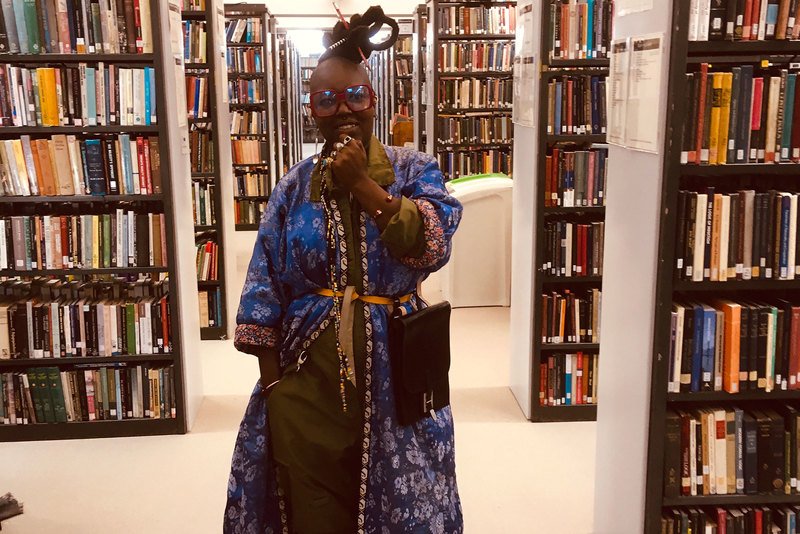

This was according to research led by Skye Chirape – a University of Cape Town (UCT) psychology PhD candidate. Her work centres the lived experiences of African sexual and gender-diverse people seeking refuge in the United Kingdom (UK). It explores the ongoing conversation on the politics of migration, security, borders of gender and sexuality, and how African sexual and gender-diverse people seeking refuge in the UK are managed and treated.

Chirape is a Zimbabwean-born national who has spent almost two decades in London. Her research forms part of the Unsettling Knowledge Production on Gendered and Sexual Violence in South Africa project – an initiative of UCT’s Department of Psychology. The project aims to conduct varied research that relates to all cis and transgender women, queer, and all marginalised genders, including non-binary people.

“There has been a global movement of people journeying to the northern hemisphere to seek refuge. And in particular, there’s also been a rise in sexual and gender-diverse folks crossing the borders for safety [to] other countries,” she said. “In the UK where our research communities are located, the government has continued to create hostile environments that make it very difficult for migrants to enter and remain there”.

UCT News asked Chirape to unpack her research, touch on the outcomes, as well as the challenges during her data gathering process.

Niémah Davids (ND): Please provide some fine points on your research?

“My research deals with questions of borders and migration, centering African sexual and gender diverse people seeking asylum in the UK”.

SC: My research deals with questions of borders and migration, centering African sexual and gender-diverse people seeking asylum in the UK. The research highlights the ways in which sexual and gender-diverse communities (LGBTQI+) and their identity are defined and controlled by the state through border controls. With idealised white bodies continuously being used as the prototype for LGBTQI+ individuals seeking asylum in the UK, the legislation that provides protection for sexual and gender-diverse asylum claimants is in conflict with that of African sexual and gender-diverse individuals’ experiences.

In my research I make use of an integrated theoretical framework, which includes trauma theory, structural intersectionality theory, and Afrocentric Decolonizing Kweer Theory to explore how individuals make sense of their experiences and how structural and institutional forms of violence are emphasised in their narratives and experiences. The study intentionally centres the process of healing and employs a decolonial, intersectional narrative analysis, which aims to humanise asylum claimants while also focusing on key social justice questions.

ND: What inspired this work?

SC: My research was inspired by several observations over the years. These include the hostility perpetuated by the UK government towards black and non-black people of colour as asylum claimants and refugees, and their overall regard for vulnerabilised communities.

It’s important to note that this hostility is harmful to asylum claimants’ and migrants’ physical, spiritual and psychological well-being, and stands in their way of accessing dignified protection. My research was conducted in response to all these issues. It was also especially important for me to centre the experiences of sexual and gender-diverse people, especially considering Africa’s struggle towards creating inclusive LGBTQI+ laws. Although historical evidence shows that people with diverse sexualities and gender expressions have always existed in Africa, many countries on the continent have continued to impose restrictive policies and LGBTQI+ legislations against sexual and gender-diverse communities, which means more and more sexual and gender-diverse Africans are fleeing their homes too. This is even the case in South Africa, a country that protects sexual and gender-diverse people in its constitution. Yet they continue to experience gender-based violence, sexual violence and transphobia.

ND: Highlight some of your research outcomes.

SC: My research focused largely on chronicling the lived experiences of sexual and gender-diverse people seeking asylum in the UK, what the process entails and how individuals are treated. The research also questioned how participants’ narratives on the asylum-seeking process implicates global relations of power and ideas around homonationalism.

“Experiences shared during the research process highlight hidden and pronounced structural violence inflicted on people migrating to the northern hemisphere from the African continent”.

Experiences shared during the research process highlight hidden and pronounced structural violence inflicted on people migrating to the northern hemisphere from the African continent. These experiences speak to narratives of insecurity and liminality; state racism and structural violence through legal exclusion and economic destitution; racism and universalised assumptions and beliefs about gender and sexuality; systemic neglect and a lack of duty of care inflicted through physical exclusion and forced social distancing.

ND: Tell us about some of the challenges that cropped up during your data-gathering process.

SC: The COVID-19 pandemic was definitely a big one. Participants were already marginalised by society and violent immigration policies and were further disadvantaged when the pandemic struck. Its widespread effects made it very difficult for them to participate in this research study. So, I needed to revise my research methodology. I needed to be creative and a lot more thoughtful in regard to the manner in which the research methodology responded to issues that cropped up for potential contributors during the pandemic.

In the end, about 20 asylum claimants from different countries on the African continent participated as co-researchers. Participants included trans non-binary people, gender non-conforming, gay, lesbian and bisexual individuals. Each co-researcher chose how they preferred to share their experiences. Some opted to share these through voice notes and WhatsApp messaging, while others documented their stories in writing; some were also in direct conversation with me. This methodology allowed for autonomy and agency and provided participants with an opportunity to think about and control the experiences they wanted to share.

“Researching and writing about trauma and violence is emotionally and spiritually taxing. Some of the experiences of trauma and violence that asylum claimants shared were very difficult to process”.

I also interviewed immigration legal caseworkers and non-governmental immigration organisation staff that support African asylum claimants and refugees. I had access to other resources like the substantiative asylum interview documents, which included deeply personal and traumatic lived experiences.

Researching and writing about trauma and violence is emotionally and spiritually taxing. Some of the experiences of trauma and violence that asylum claimants shared were very difficult to process. But I intentionally put in place a PhD care plan to support the journey and manage any experiences of vicarious trauma. Being a member of the Unsettling Knowledge Production project has also been beneficial. Collaborating and co-writing alongside other scholars about what it means for us to conduct and engage with research that interrogates issues related to trauma and violence has offered me a tremendous amount of support.

ND: Your topic of choice explores and evaluates deeply personal and sensitive narratives. What about the process in its entirety has been most fulfilling?

SC: The process of co-creating and co-producing knowledge with asylum claimants was most rewarding. Every individual who contributed to the study provided valuable knowledge and experiences that offered crucial perspectives to the research. The process we adopted allowed us to reimagine methodological practices while challenging some of the traditional and previously normalised ways of conducting psychology research.

ND: Your research on communities living on the margins of society is critical and contributes significantly to a larger ongoing discourse. What kind of impact are you hoping your work will have?

SC: I hope this work will provide a different perspective to the larger conversation on borders and the violence on borders, and a framework on how co-creation and collaborative knowledge production with marginalised co-researchers in the field of psychology can look like.

The study focused on reimagining psychology methodologies and how they can serve as a catalyst for healing. We deliberately focused on adopting remedial practices that offered a space for practical support and resources that aimed to improve asylum claimants’ lives, especially during the pandemic. We hope that the methodology provides an example of how such work might look for other types of psychology research, conducted with communities who are on the margins of society.

“The research taps into where forensic psychology should be to respond to the world as it is right now”.

Lastly, the field of forensic psychology currently overlooks migration and refugee experiences despite the intersection with forensic settings. With increasing levels of migration and confrontation between migration, especially the asylum process and the criminal justice and forensic settings, the research taps into where forensic psychology should be to respond to the world as it is right now.