- Diaspora

- No Comment

‘Black tax’ – Zim diasporans weigh into campaign to stop sending money back home

By BBC News

“Sending money back home or to your extended family is such a common African practice that I absolutely hate,” said Kenyan influencer Elsa Majimbo in a now-deleted TikTok rant that sparked a furious debate on social media.

The 23-year-old, who shot to fame during the covid pandemic with her comedic videos, touched a nerve when it came to discussing with her 1.8 million followers what is known as “black tax”.

This is when black Africans who achieve a modicum of success, whether at home or abroad, find themselves having to support less well-off family members.

Giving back is seen as an intrinsic part of the African philosophy of ubuntu, which stresses the importance of the family and community, rather than the individual.

The question for many is whether this is an unnecessary and unwelcome burden or part of a community obligation to help pull others up.

But Ms Majimbo, now based in the US, is pushing back against the practice.

In the video she said her father had supported members of the extended family for years and now they were looking to her for help. She turned her anger on one particular unnamed relative.

“You’ve been asking my dad for money since before I was born. I was born, I was raised, I grew up, now you’re asking me for money – you lazy [expletive]. I’m not feeding your habits.”

While some have agreed, others have taken issue with her position. It is not clear why the video was removed from TikTok and Ms Majimbo’s management team did not respond to a request for comment.

But for many, regardless of what they might personally think, it is just not possible to refuse to help relatives because of the sense of community in which they were raised.

There can be a sense of pride in helping take care of the family although it can become too much.

There needs to be a balance between bearing this financial responsibility and your personal financial health”

A former teacher in Zimbabwe in her 50s, who asked to remain anonymous, told the BBC that 30 years ago almost her entire first pay cheque of 380 Zimbabwe dollars went straight to her nine siblings.

“After I finished buying [school] uniforms, clothes and groceries, I had $20 left,” she told the BBC in a voice that suggested both honour and annoyance.

Although this meant she had to buy food on credit, she said that as the eldest child it was expected she would hand over cash the moment she began to start earning.

Her salary did not belong to her alone but to her family as well.

When she got married, her responsibilities extended even further. At one point, she had to take out a loan to pay her brother-in-law’s tuition fees after she was pickpocketed on her way to deposit a cheque at the bank. It took her two years to pay off.

Dr Chipo Dendere, an assistant professor in Africana studies at Wellesley College in the US, argues that the necessity of “black tax” is rooted in colonialism.

The system of oppression that concentrated resources in the hands of the colonial power or a tiny minority of settlers made it impossible for the majority to accumulate assets.

This “left many black families with no generational wealth”, Prof Dendere said.

In many cases, after independence, rather than being upended, the inequalities were replicated.

Dr Dendere added that the payment of “black tax” can often become a “never-ending cycle” as the money sent to family members often only temporarily plugs a hole which will later re-open.

Another factor is that, unlike in richer countries, many African states are unable to pay for healthcare beyond the basics, provide a decent pension or cover tuition fees. As a result it falls on the most well-off in a family to fork out for these expenses, Dr Dendere said.

“There is no pension fund from the state – we are the pension. Families are stepping in to do the job of the government.

“We give because of ubuntu. We are forced to take care of each other.”

In 2023, funds sent home by African migrants amounted to about $95bn (£72bn), according to the International Fund for Agricultural Development.

For Zimbabwe, the flow of remittances is huge and crucial for a long-struggling economy. Diaspora remittances from outside the country are estimated at over US$1 billion per annum, or around 16% of total foreign exchange receipts.

However, Africans abroad the strain can be even greater as people expect more due to a belief that those overseas make a lot of money.

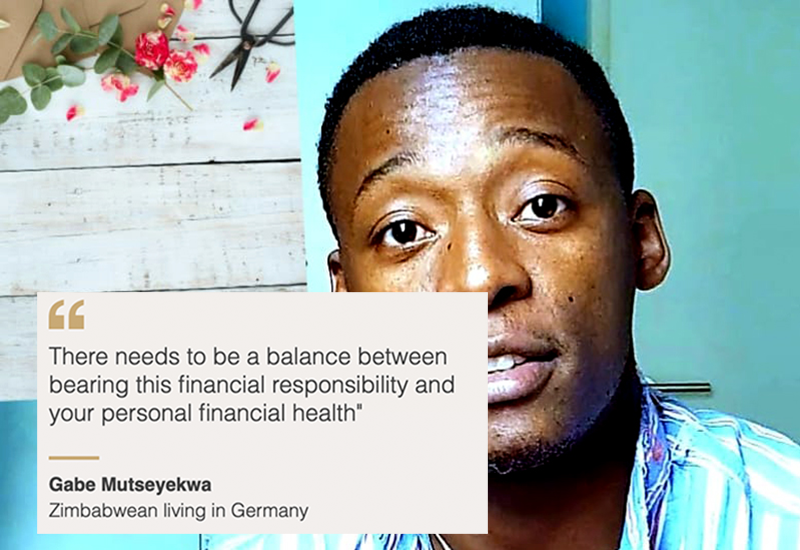

Gabe Mutseyekwa, 35, is a Zimbabwean man who has lived in Germany for over five years. He put his foot down and told his family he would stop sending monthly payments because it was preventing him from saving up for his own future.

His family did not react well – but they eventually came around.

“They realised that I was all alone and I needed to make something of myself,” he said.

At one point he sent home about €2,000 ($2,200; £1,700) for a family emergency when he was still a student doing part-time jobs.

“There needs to be a balance between bearing this financial responsibility and your personal financial health,” he told the BBC.

Many people have noted that family members can feel a sense of entitlement to your money especially when the person is rich.

While not everyone agreed with Elsa Majimbo’s rant, it seems to have touched a nerve, especially among the younger generation.

But Dr Dendere argues that unless Africa can truly develop, “black tax will be here in perpetuity”.