- Featured

- No Comment

IN-DEPTH: Zimbabwe faces endless exodus of health workers amid poor salaries and worsening conditions

By Jeffrey Moyo for Health Policy Watch

HARARE: After a decade of service as a nurse in the public sector and very little to show for her years of toil, Letina Chiwongotore has thrown in the towel.

The 35-year-old is packing her bags for the UK, no longer able to bear mounting economic hardships.

Nurses, doctors, pharmacists and other healthcare staff have been fleeing for several years to escape low salaries and poor working conditions in a country that seems unable to overcome its economic problems.

Earlier this year, the Zimbabwean government converted the $300 COVID allowance it had been paying to nurses to a permanent salary. Nurses now take home an average of $255 every month after tax.

The payment in US dollars, although small, has been welcomed by the Zimbabwe Nurses Association (ZINA) as nurses had previously been paid in local currency. With hyperinflation, the local currency had almost completely lost its value, rendering the nurses’ salaries and pensions of retired nurses virtually worthless.

However, this salary is substantially lower than that paid back in 2018 when nurses received $540. Meanwhile, civil servants’ organisations estimate that the minimum wage should be $840.

Years of brain drain

Zimbabwe’s health care system has been crumbling under the strain of decades of brain drain, fuelled by economic and political instability since the late 1990s, which has caused high inflation and the collapse of the local currency.

Health workers’ salaries have not been spared the inflation amid currency woes, forcing many professionals to migrate in search of better opportunities abroad.

By 2000, 51% of Zimbabwe’s doctors and 25% of its nurses were already practising abroad. By 2019, the UK’s National Health Service employed 4,049 Zimbabwean healthcare professionals including doctors, nurses and clinical support staff.

As if that was not enough, more than 4,000 health workers, including more than 2,600 nurses, left Zimbabwe in 2021 and 2022 alone, according to official statistics.

Aside from the UK, health workers have sought employment in Canada and Australia.

Between September 2022 and September 2023, some 21,130 Zimbabweans were given visas to work in the UK, many of those being nurses and care workers, according to that country’s Home Office data.

Late last year, the World Health Organization (WHO) went on record, saying that 4,600 Zimbabwean health workers had left the country since 2019.

Crippling effect on health

The brain drain of health professionals from Zimbabwe has had a crippling effect on the country’s public health system and on health outcomes.

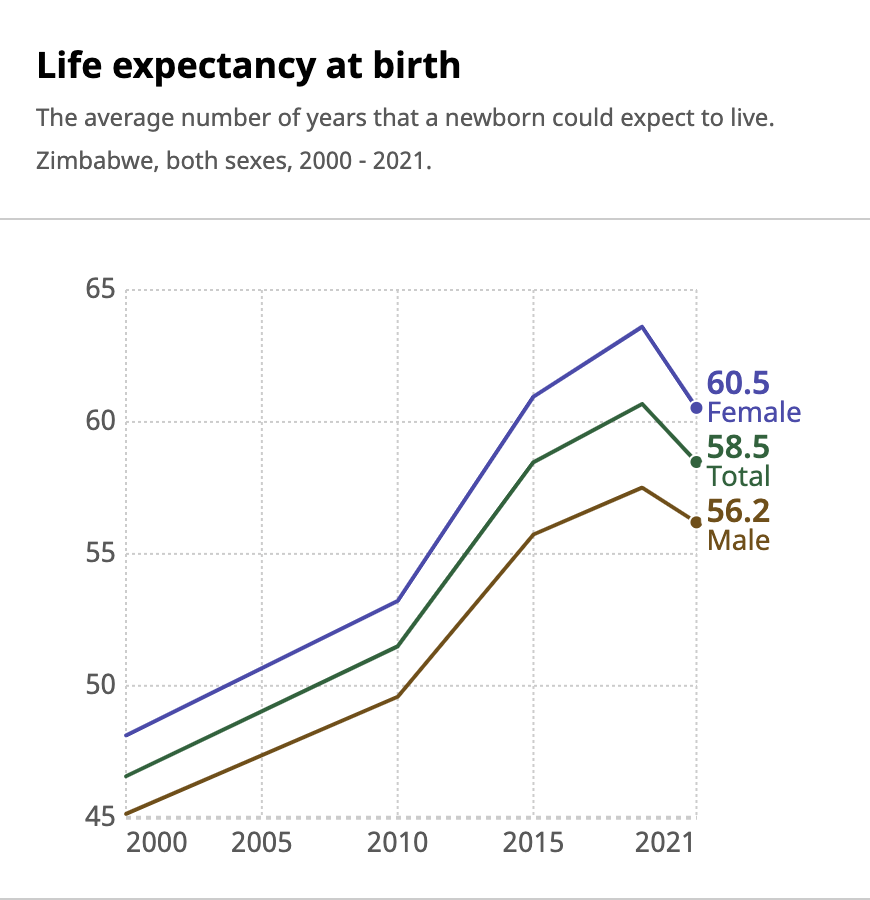

For example, in 2021 life expectancy was 58.5 years, a two-year drop from the already low 60.7 years in 2019, according to WHO figures. This is also lower than the average life expectancy for Africa, which was 63.6 years in 2021.

The growing shortage of healthcare workers is endangering the lives of patients in hospitals that are already poorly equipped.

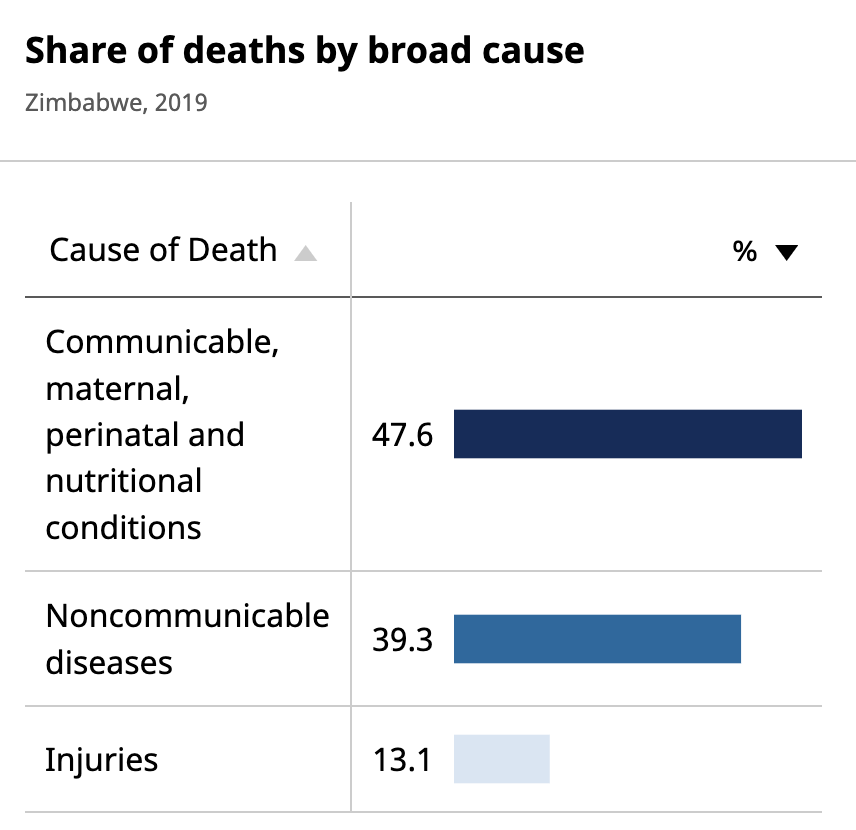

HIV, respiratory tract infections and neonatal conditions – mostly preventable and treatable – are the three biggest killers. Tuberculosis infection has worsened since 2021. Infectious diseases, maternal, perinatal and “nutritional conditions” including malnutrition are responsible for 47% of deaths. However, non-communicable diseases are on the rise, accounting for almost 40% of deaths.

The few Zimbabwean nurses that remain in the country’s crumbling healthcare facilities are having to attend to ballooning numbers of patients.

This has caused a domino effect, accelerating the exodus of health workers who cannot manage the work load and face daily demoralisation in under-resourced facilities.

Melina Chiwara, a 28-year-old nurse, says that she is struggling to cope with the growing workload and deteriorating working conditions.

Chiwara, like thousands of others who have left the southern African nation, says that she too will soon join the quest for a better life abroad as she can no longer manage.

Government withholds proof of qualification

Desperate to stem the brain drain, the government has resorted to withholding the verification letters that thousands of nurses and doctors need to secure jobs abroad. These letters confirm health workers’ qualifications.

In addition, it is time-consuming and costly to get a passport.

Incensed by the ongoing recruitment of health workers by wealthy countries, Vice President Constantino Chiwenga threatened legal action last year against the recruiting countries.

“If one deliberately recruits and makes the country suffer, that’s a crime against humanity. People are dying in hospitals because there are no nurses and doctors. That must be taken seriously,” said Chiwenga.

However, despite the challenges, many qualified health workers are still opting to leave, taking lower-paying jobs as care workers in the UK in particular, as these jobs will enable them to support families back home.

“I will be going to the UK because I can’t keep on offering my nursing services for peanuts. I am tired. If I don’t get all my relocation papers in order, I will settle for any dirty job in the UK and at least earn something [more] meaningful than remaining in this jungle,” Chiwongotore told Health Policy Watch.

‘The heart belongs at home’

Nurse Setfree Mafukidze relocated to the UK three years ago with his wife and four children. For years, Mafukidze had toiled at a clinic in Chivhu, a town located approximately 140 kilometres south of the Zimbabwean capital, Harare.

Now living in Somerset in the UK, Mafukidze asserts that “most nurses are better off outside Zimbabwe than they were in Zimbabwe.” The starting salary is around $34,000 per month.

“Nurses earn enough to survive within the UK because most of the nurses are not required to pay school fees for their children if they have any,” said Mafukidze.

“They don’t need to pay for healthcare services either unless one chooses to go private. The normal healthcare services here are always free for nurses, while in Zimbabwe if a nurse falls sick, you need to do crowdfunding to help them – yet they are the people that sustain the healthcare,” said Mafukidze.

Since Zimbabwe was placed on the WHO ‘red list’ of countries with critical health worker shortages, the UK has stopped recruiting its health workers.

News of not-so-rosy conditions have also started to filter back to remaining health workers.

“It’s unfortunate that, with the UK now being flooded by migrant healthcare workers, shifts for care workers are now scarce. I have heard of inflation and increased cost of living there as well. I no longer see myself leaving any time soon,” said Warren George, a 30-year-old nurse who has opted to stay in the country.

For those nurses already abroad, even as they pride themselves after fleeing from Zimbabwe, they remain attached to their country despite the odds.

“The heart belongs home. Most nurses and doctors want to be home, but home doesn’t provide the tools for the trade. Home doesn’t provide good mental care to its workers,” said Mafukidze.